Even back in the Thirties, anyone watching the scene might have guessed they were witnessing the end of an era.

Shortly after lunch, the grand doors of Longleat, one of Wiltshire’s most celebrated stately homes, were thrown open and two rows of liveried footmen hurried out to line up on either side of the steps leading down to the drive.

After a short pause, two figures duly emerged, blinking in the sudden sunlight.

One, resplendent in his frock coat, was the old Lord Bath, one of the most courteous aristocrats of his day. The other was a handsome young man, politely pouring praise on the glories of the house and quietly pretending that this was the sort of thing that happened every day.

There would have been an awkward moment as Lord Bath waited for his guest’s transport to be brought round to the front. But it already had; the rusty bicycle being held gingerly by a footman at the bottom of the steps was his guest’s transport. The man from the National Trust was leaving in the same way he’d arrived – on his bike.

What James Lees-Milne, the young man on that bicycle, would always remember, however, was pausing after he had pedalled some considerable way down the long straight drive and turning for a last admiring look at the house.

There, still, was Lord Bath, flanked by his two rows of footmen, waiting at the top of the steps, impeccably observing the old-world tradition of remaining in view until one’s guest was out of sight.

It didn’t matter that the meeting had been unsuccessful, that Lord Bath would not be donating Longleat to the Trust.

That was the pattern of things, as Lees-Milne soon realised; at some grand houses he never made it past the front door, at others he was welcomed with open arms by families desperate to relieve themselves of the financial burden.

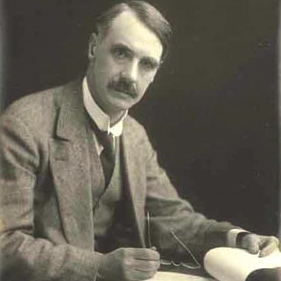

Lees-Milne – Jim to his friends and destined to become one of the most celebrated diarists of his day – had embarked on the work that more than half a century later would cause him to be described as ‘the man who saved England’.

What the 28-year- old Oxford graduate was engaged in was saving England’s stately homes – and one or two in Wales, too.

It was his pioneering work to persuade their aristocratic owners to donate their houses to the National Trust that helped turn it into the hugely successful institution that it is today, with more than 300 houses and 3.5 million members.

But back in the Thirties the Trust – already 40 years old but with barely 5,000 members – owned almost no grand country houses at all. That situation would slowly change, as Jim criss-crossed the country, searching for houses of sufficient architectural merit to justify the Trust acquiring them, and to begin the often tortuous process of persuading their aristocratic owners to part with them, often after centuries of family ownership.

But Jim, as charming and tactful as he was good-looking, was both persuasive and patient. One by one, some of the most important stately homes in Britain passed into the Trust’s ownership, a process that accelerated significantly during World War II, as more and more owners realised the old order of things had gone for ever.

Jim, who was invalided out of the Irish Guards in 1941 after being caught in a bomb blast and developing a rare form of epilepsy, returned to the National Trust and found himself busier than ever, his work bringing him into daily contact with the rich tapestry that was England’s often highly eccentric aristocracy.

Some owners received him in bed in their nightcaps, others took him to the estate pub; one particularly blimpish owner even proudly took him up to the tower to show him how he peppered the nearby lake with rifle-shots in winter to stop the locals skating on the ice. Jim took it all in his increasingly practised stride.

His success seemed hardly surprising. Born to a landed Worcestershire family and educated at Eton and Oxford at a time when both establishments were shamelessly elitist, Jim – as he flirted with elderly duchesses and politely deferred to curmudgeonly dukes – was, to outward appearances, simply mixing with his own sort of people.

But all was not as it seemed. Jim’s father, George, had derived his fortune mainly from a Lancashire cotton mill and he had bought the house, Wickhamford Manor, where Jim was brought up, only two years before his son was born.

At a time when to be so closely associated with ‘trade’ could have spelt social death, it’s not surprising that Jim kept fairly quiet about his background, simply describing his family as ‘lower upper class’.

However, as Michael Bloch’s fascinating new biography reveals, Jim had another secret, known to his circle of immensely well-connected friends – many of whom seem to have stumbled out of the pages of an Evelyn Waugh novel – but not to the outside world.

He was bisexual and, indeed, as a young man was rather keener on going to bed with men than with women.

At school and university, he had a steady succession of male lovers. At Eton, his great affair was with Tom Mitford, brother of the later famous Mitford sisters; at Oxford, his lovers included the future Colonial Secretary Alan Lennox-Boyd, and an up-and- coming young actor called John Gielgud, who would treat him to meals at the Spread Eagle tavern in Thame.

One of his greatest romantic interests was the fellow conservationist Rick Stewart-Jones.

But unlike many of his homosexual friends, Jim also enjoyed both the company and the physical charms of women.

Having lost his virginity at the age of 17 to a voluptuous, recently divorced cousin, Jim – a hopeless romantic – would fall sporadically in love with women for the rest of his life.

An early object of his affections, which were welcome but not wholly reciprocated, was Diana Mitford, to whom he was attracted not only because she was the most beautiful of the Mitford girls, but because she reminded him of his Eton flame, Tom.

Shortly after coming down from Oxford in 1931 and finding himself with little idea of what to do next, Jim worked as a political campaigner for Sir Oswald Mosley, who had founded his New Party in 1930 (he would not embrace fascism until 1932) and was now fighting the General Election.

Mosley, whose aunt had married Jim’s uncle, had not yet met his future wife Diana Mitford, with whom Jim had recently been in love.

Mosley lost in Stoke-on-Trent, but not before Jim had met another New Party candidate, someone who was to become one of the most influential figures in his life – Harold Nicolson, ex-diplomat and man of letters who combined marriage to Vita Sackville-West – the poet, author and celebrated creator of the garden at Sissinghurst in Kent – with a penchant for the company of intelligent, always handsome young men.

What the world knows now, of course, but was then known only to a select few, was that the Nicolson-Sackville-West marriage was highly unusual.

While devoted to each other and having produced two sons, they were both basically homosexual and allowed each other complete freedom to pursue their respective sexual interests.

Within two years, Nicolson was pursuing his interest in Jim with enthusiasm. He frequently invited him to dinner in London and, in 1934, whisked him off to Paris (while Vita was in Italy conducting an affair with Harold’s sister, Gwen St Subyn).

It was in the French capital that he introduced the impressionable 25-year-old, with his youthful passion for famous writers, to James Joyce, author of the acclaimed but controversial novel Ulysses.

In his subsequent and discreetly worded letter to Jim, Nicolson, 22 years his senior, encouraged the younger man to have no regrets about what had passed between them on that trip.

It was, he wrote, quite possible to derive both affection and tenderness from contacts that others might find objectionable.

Jim and Harold were to remain close friends for the rest of the older man’s life.

Jim would live with him at his London flat in Kings Bench Walk, and seek his urgent advice when he fell in love with – and for a time became engaged to – Lady Anne Gathorne-Hardy (Nicolson advised that the basis of a successful marriage was intelligence and esteem, not physical lust).

And it was Harold’s influence, after a tip-off from Vita, that secured Jim the job at the National Trust.

Jim may not have been entirely surprised by the Nicolsons’ unusual arrangements. His own mother and father both had flings and longstanding affairs during their nevertheless enduring marriage.

His beautiful and flirtatious mother, upon whom Jim had doted as a child, ended World War I far closer to Jim’s dashing, polo-playing godfather then she was to her own husband.

Not surprisingly George Lees-Milne, a man whose main passions were hunting, shooting and fishing, and who disapproved so strongly of his son’s ‘cissiness’ that he denied him financial assistance, sought consolation elsewhere.

Given the example set by his parents and the Nicolsons, Jim may have had something similar in mind when, in 1951, at the age of 43, and to the surprise of his friends, he decided to get married himself.

What he couldn’t have known, however, was how miserable what ensued would make him.

The object of his heterosexual affections was Alvilde Chaplin, a wealthy heiress who was still married to her first husband when Jim met her.

There is no doubt he was genuinely smitten – Alvilde was intelligent, sharp and an accomplished hostess and organiser.

Perhaps too equine to be described as pretty, Jim would later describe her beauty as ‘proud, guarded, even shrouded’. But, as others had already discovered, she could also be aloof, impatient, dictatorial, argumentative and possessive.

Even her unusual Christian name should have been a warning. Her father, General Sir Tom Bridges, was, as well as being a successful soldier and diplomat, a notorious philanderer.

While serving with military intelligence in Scandinavia, he had conducted an affair with a Norwegian ballerina of that name.

When his pregnant wife, Janet, discovered the affair, it is said she insisted on giving the child the name of his mistress as a permanent reminder to her husband of his adultery.

Alvilde confessed to Jim that, as a girl, she had herself succumbed to her father’s sexual advances. Small wonder – especially after her first husband turned out to be another serial seducer of young women – that she preferred the company of sexually ambiguous men such as Jim.

But, like Vita Sackville-West, Alvilde also enjoyed the company of women; indeed in Paris in 1937, tormented by her husband’s infidelities, she began a long lesbian affair with the city’s great musical hostess, Princess Winnie de Polignac. The Princess was 72 at the time, Alvilde just 27.

Jim, who had met Alvilde with the Princess shortly before the latter’s death in 1943, would have been aware of this when, six years later, he started seeing Alvilde regularly in London. (She was now a rich woman, having inherited a slice of the Princess’s enormous fortune.)

Jim had a habit of falling in love with people who reminded him of others he had known in the past and in Alvilde’s case, it seems that her determined personality reminded him of Kathleen Kennet, the sculptor and widow of the polar explorer Captain Scott, with whom Jim had forged a deep friendship as a young man that had bordered on the erotic.

Jim’s romance with Alvilde proceeded at some pace; a succession of dinners and trips to the theatre and cinema was eventually followed by a holiday in Italy, which not only saw Jim having to borrow money to get there, but was taken with Alvilde’s zoologist husband, Anthony, in full attendance.

Anthony was quite relaxed about the relationship, as throughout his marriage he enthusiastically pursued women on his own account.

Jim had fallen in love with Alvilde, writing in his diary. ‘My mind a turmoil. A fire has been lit.’ It was, he said, the first time his love for a woman had been fully reciprocated.

Alvilde divorced her husband and, on November 19, 1951, she married Jim at Chelsea Register Office, despite his concerns about her argumentative and possessive nature.

There were four witnesses, including Harold and Vita and James Pope Hennessy, the exotically handsome and quick-witted young man who had taken Jim’s place in Harold’s life.

Two more couples joined the party for lunch, and Jim must have taken quiet reassurance for the matrimonial life ahead that of the five men present, including the three husbands, all were homosexual; three of them being his own ex-lovers.

It may also not have escaped Jim’s notice that of the women present, at least two had experience of lesbian relationships: Vita, obviously, and Alvilde.

Married life did not work out quite as Jim had presumably planned, although for the first few years the couple were happy, helped by the fact that for part of the year they lived apart – Alvilde in tax exile in the south of France, while Jim returned to London to work part-time for the National Trust and to resume his bachelor lifestyle.

These periods of separation worked as a safety valve.

It’s not clear when the unhappy aspects of his marriage began to outweigh the happy ones, but certainly by 1958, Jim felt trapped in a union he considered a mistake.

Alvilde had declined to have further sexual relations with him. For a still highly physical man, this must have been a terrible blow and Jim compensated with a series of transient homosexual affairs.

Why had she gone off sex with her husband? There was one possible, if extraordinary explanation: Alvilde had abandoned herself to a passionate lesbian affair with Vita Sackville-West, whose husband had, of course, been Jim’s lover 20 years previously.

Alvilde said nothing to Jim about the affair until it was almost over, and nor did Vita mention it to Harold. But Jim certainly knew about it, given that letters arrived for Alvilde from Vita ‘almost daily for several years’.

Those letters – now archived in New York Public Library – make it clear that by 1955 the two women were much in love, although Vita was racked with guilt for the potential hurt it would do Jim, who had been her friend for almost as long as he had been Harold’s.

But finally, at Sissinghurst, on October 26, 1955, under a full moon, their love was consummated.

Alvilde’s growing and genuine passion for gardening gave her the pretext for visits to Sissinghurst, and Vita’s letters to her lover began to be spiced with love-verses.

Vita, however, whose past loves included socialite Violet Trefusis and novelist Virginia Woolf, was as famous for her lesbian passions fading as she was for starting them in the first place, and in 1957 she wrote to Alvilde bringing their affair to a close. There could be no more ‘LL’ – lesbian love. Alvilde was consumed with grief.

In the circumstances, Jim could be forgiven for thinking that his own romantic adventures would now be tolerated by Alvilde, but he couldn’t have been more wrong. With Vita out of her life, Alvilde turned her famous possessiveness on her husband.

So when, in October 1958, shortly after his 50th birthday, Jim fell desperately in love, a marital crisis loomed. The object of his considerable affections was a handsome 27-year-old who, ironically, was introduced to him by Harold Nicolson.

Harold hoped Jim would be able to help the young man, who had an extensive knowledge of both architecture and sculpture, to get a job at the National Trust, just as Harold had helped Jim more than 20 years earlier.

Jim and his protege were immediately attracted to each other, with Jim no doubt seeing a reflection of his own youth in the younger man. Almost overnight, his mid-life melancholia turned to euphoria. However, when Alvilde learned of Jim’s love for his new friend, she hit the roof.

After her suspicions had been confirmed by steaming open a few letters (a habit that was to stay with her for the rest of her life), she confronted Jim. Believing her own affair with Vita had set a precedent, Jim confessed freely. It was a dreadful mistake.

Alvilde was consumed with jealousy. Terrible scenes ensued, and many of their friends regarded the marriage as doomed.

Although relations between Jim and Alvilde were never quite the same again, and she remained both suspicious and jealous of his male friends, the marriage endured.

What saved it was their discovery of a house they both adored in the Cotswolds, where they went to live in 1961.

Alderley Grange, a Jacobean house with Georgian additions, was of sufficient architectural interest to satisfy Jim, while its large garden enabled Alvilde to indulge her passion for gardening, which had been encouraged by Vita (and which would later result in a new career designing gardens for such celebrities as Mick Jagger).

It was, to all intents and purposes, their Sissinghurst and would keep them busy for years. They would live there – increasingly happier as they got older – for the next 14 years.

The man who saved England, the man who had bicycled his way up so many an aristocratic drive, had been saved by his own little corner of English country life.