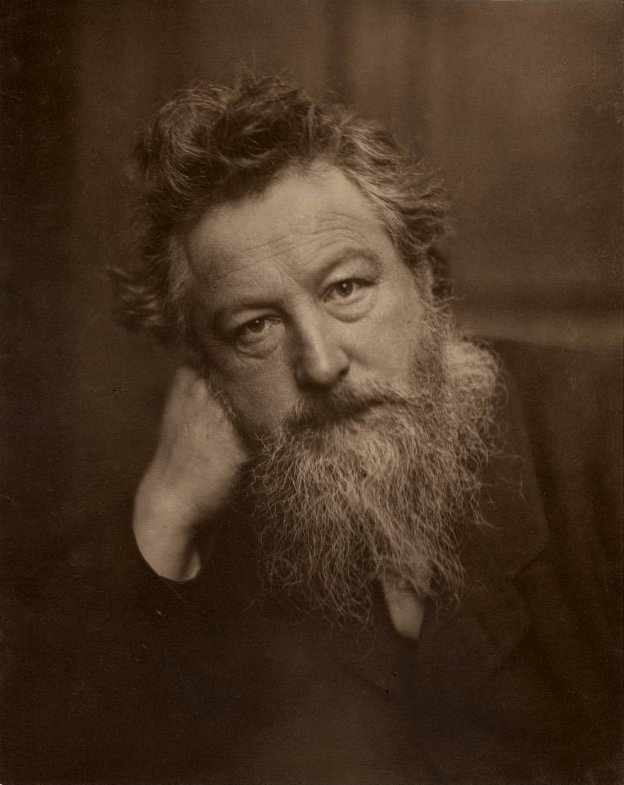

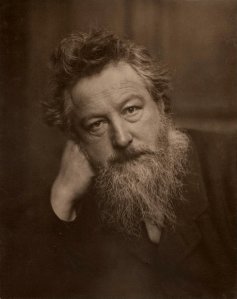

William Morris (1834-1896) is regarded as the greatest designer and one of the most outstanding figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement. He was also a poet, artist, philosopher, typographer and political theorist. In 1861, with a group of friends, he started the decorating business Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. which provided beautiful, hand-crafted products and furnishings for the home. This was highly controversial at the time as it denounced the ‘progress’ of the machine age by rejecting unnecessary mechanical intervention. Influenced by the ideas and writings of Thomas Carlyle and John Ruskin, who sought to re-dress class inequality and improve society by reinstating the values of the past, Morris was motivated by the desire to provide affordable ‘art for all.’

Driven by his boundless enthusiasm, the output of the company was prolific and encompassed all the decorative arts. He is perhaps best known for his wallpaper and fabric designs but he also designed and made embroideries, tapestries and stained-glass, reviving many of the traditional arts which had been swept away by industrialisation. Before he mastered each craft, he learnt every stage of the hand making process and understood his materials thoroughly so that he could get the best results and teach others.

Over the next 150 years, Morris & Co. enjoyed long periods of exponential growth but also suffered significant downturns from poor direction and the turbulent years of the First and Second World Wars. Some of the stories behind the history are told here but this is by no means an exhaustive account. We bring you an overview of the origins, achievements and landmark events that have taken place.

At the bottom of this page we have provided Further Reading to direct you to just some of the publications and resources on this expansive and fascinating subject, and the life and times of William Morris. Following this, in Places to Visit, we have identified beautiful and inspiring houses decorated in original Morris & Co. furnishings and decorative art where you can learn about the people who followed his principles on interior design and shared his passion, or were in his immediate circle and influenced his work and ideas.

WILLIAM MORRIS

‘I DO NOT WANT ART FOR A FEW, ANY MORE THAN EDUCATION FOR A FEW, OR FREEDOM FOR A FEW.’

William Morris was born in Walthamstow in 1834, into a wealthy middle-class family, and brought up in a large household unusually imbued with the spirit of the Middle Ages which influenced the clothes they wore, their pastimes, their home furnishings and even the food they ate. The eldest son of nine children, Morris’s father was a successful broker in the City of London and the family leased many houses during his childhood. When he was fourteen and still at boarding school, the family moved into Water House (now the William Morris Gallery) where Morris spent his school holidays exploring the idyllic rural surroundings.

Morris developed an early appreciation of the beauty of nature honestly expressed through literature and art. He was equipped with a strong moral and social compass which inspired his utopian views of how a fairer society must be achieved in an age of class division. When he was seventeen, London was showcasing the very best of British manufacturing, art and industry at the 1851 Great Exhibition. Morris refused to enter, repelled by the ‘ugliness’ of what he expected to find there.

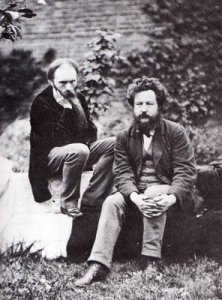

When Morris was at Oxford University studying theology he met Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), and they became interested in the notion of living in an artistic community brought together by a shared purpose. He wanted to return to the medieval system that supported craft through the notion of artisan guilds (which revered and valued the artist) at a time when the status of the individual maker had been diminished by the mechanisation of the industrial revolution.

Disillusioned by his chosen career, Morris dropped out of University and pursued a profession in architecture where he met the designer and architect, Philip Webb (1831-1915). Shortly after, he switched to painting, became part of a group of artists self-named the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and achieved some success. Morris married Jane Burden in 1859. He had already begun publishing his own poetry, and at this time was better known as a poet than an artist.

Whilst on a trip to France to study gothic cathedrals and castles, Morris and Webb discussed the idea of designing and building a house – a home for Morris and an artistic community which he and Burne-Jones had dreamt of since their university days. Work started as soon as they returned to England, and in 1859 Webb designed a red brick house in the medieval style for Morris and Jane. After they moved in Morris and his friends set about decorating ‘Red House’, as it became known, with a shared vision and in the spirit of creativity and freedom of expression.

WILLIAM AND JANE MORRIS MOVED IN TO RED HOUSE IN THE SUMMER OF 1860 AND WERE FREQUENTLY VISITED BY FRIENDS, ESPECIALLY BURNE-JONES AND HIS NEW WIFE (THE ARTIST GEORGIANA MACDONALD), ROSSETTI AND HIS WIFE AND MUSE LIZZIE SIDDAL, AND CHARLES FAULKNER.

Collectively they all helped decorate and furnish the house – nothing was factory made. Huge murals were painted on the walls and in the dining room; William and Jane were depicted as king and queen at a medieval wedding banquet. Most of the ceilings were painted in small geometric patterns, the designs pricked out in the plasterwork, which still look modern today.

Morris brought in antiques, Persian carpets, ironwork and the large wardrobe depicting Chaucer’s ‘Prioress Tale’ from ‘A Canterbury Tale’, a wedding present, hand-made and decorated by Burne-Jones and Webb. However, Morris struggled to find new furniture and decorative objects in the simple gothic style, so Webb made candlesticks, fire-irons, grates and new furniture often lavishly painted in scenes from literature. Burne-Jones and Webb created numerous stained glass windows, some depicting naïve medieval animals and plants.

Instead of wallpapering, they embroidered fabric hangings to line some of the walls. Morris, self-taught in medieval embroidery techniques, instructed Jane and her sister Bessie to help carry out the work. He designed a simple ‘Daisy’ motif, inspired by a 15th century Dutch illuminated manuscript, which they embroidered onto indigo wool serge. She wrote ‘we worked in bright colours in a simple, rough way – the work went quickly and when we finished we covered the walls of the bedroom at Red House to our great joy’.

Then, Jane and Bessie embarked on a much more ambitious project – to embroider 12 large hangings, designed by Morris, depicting ‘Illustrious Women’ from the works of Chaucer. Reminiscent of stained glass design, the heavy-outlined figures were intended to be cut from the cloth and appliquéd onto wool serge to hang in the drawing room.

THE GARDEN

The medieval inspired walled garden was formally arranged using wattle trellis and retained some of the original orchard. Webb and Morris carefully researched and selected plants for the garden: native Ayrshire rose and Aaron’s rod and exotic passion flower. The informal planting scheme of lilies, sunflowers, lavender, honeysuckle, jasmine and rosemary all mingled against the climbers which Webb advised would disguise the look of new brick.

Leading from the back door, there is a small covered porch with bench called the ‘Pilgrim’s Rest’, decorated with tiles designed by Burne-Jones and Morris. Georgiana wrote that this was where they ‘sat and talked and looked out into the well court, of which two sides were formed by the house and the other two by a tall rose-trellis’ and which ‘summed up the feeling of the whole place’.

Jane gave birth to a daughter, Jenny, in 1861 and a second daughter, May, in 1862. Georgiana Burne-Jones’s first son Philip was also born in 1861.

Inspired by their success, they turned their experience into a decorating business in 1861 under the name Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Company. The founding members were: William Morris, the painters Edward Burne-Jones, Ford Madox Brown (1821-93) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-82), an engineer and amateur artist Peter Paul Marshall (1830-1900), the architect Philip Webb, and the company’s book keeper Charles James Faulkner (1833-92).

How the partners’ lives became inextricably linked is itself a fascinating story centred round one particular radical art scene that crossed social and cultural boundaries. These introductions were soon to meld into an extraordinary group of people who went on to revolutionise art and interior design in the Victorian era

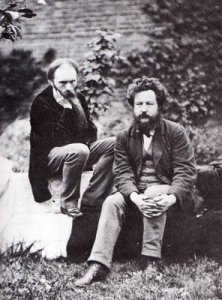

THE FOUNDERS OF MORRIS, MARSHALL, FAULKNER & CO.

Morris’s first career choice was to go into the Church and in 1853 he enrolled to study theology at Oxford University where he became life-long friends with fellow under-graduate Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898). Burne-Jones had attended Birmingham School of Art, but intended to become a church minister. They were intrigued by the idea of reviving the medieval tradition of living and working in a monastic community, a metier which Morris had held since he was a boy. The two men also had an interest and talent in the arts, both influenced by the Arthurian subjects and romanticism of the painter and poet, Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882).

Rossetti trained at the Antique School at the Royal Academy of Arts and found inspiration in the naturalism and purity of the art produced before the classicism of Raphael. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) in 1848, along with William Holman-Hunt and John Everett Millais, and set about reforming and challenging the conventional art establishment through paintings rich in symbolism, nature and colour. Rossetti studied under the painter Ford Madox Brown (1821-1893), whom he greatly admired. Brown was known for his paintings with a strong narrative and moral message and although he never became a member of the PRB, he was closely associated with its members.

Brown exhibited at the Liverpool Academy in the early 1850s and it may have been here that he met amateur artist Peter Paul Marshall (1830-1900), a civil engineer from Scotland. Brown introduced Marshall to the members of the PRB in London and he later married the daughter of one of their patrons.

After a tour of France visiting Gothic cathedrals and an exhibition of Pre-Raphaelite art in Paris in 1855, Burne-Jones and Morris reconsidered their careers: Burne-Jones dropped out of University to become a painter and set up a studio in Red Lion Square, London. He and Morris founded the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine which gave a platform to their views on the arts. Rossetti contributed articles to the paper at their request and it was then that the three were finally to meet. Rossetti became a mentor to Burne-Jones and actively supported him in his artistic endeavours. Morris was now being drawn to architecture and he secured himself an apprenticeship with Gothic Revivalist George Edmund Street in Oxford in 1856 where he trained under Philip Webb (1831-1915).

Philip Webb grew up in Oxford and developed an appreciation of the domestic and ecclesiastical buildings of that historic city and surrounding villages. He was a talented artist and decided early in life to become an architect. One of his first short-lived employments was in Wolverhampton but the harsh reality of an industrial manufacturing town and ugly modern urban sprawl drove him back to Oxford where he worked with G.E. Street in 1854.

Webb and Morris were relocated to London when Street’s practice moved to the city. Morris shared lodgings with Burne-Jones in Red Lion Square, but became increasingly frustrated with architecture and longed to create with his hands, not just design on paper. In 1856, encouraged by Rossetti, Morris found the courage to abandon architecture and become a painter. Financially independent, Morris was privileged to enjoy the life of an artist without having to earn a living; his paintings received mixed reviews.

Their first commission, in 1857, was to paint murals on the upper walls and ceiling in the new Oxford Union debating chamber in 1857. They were helped by Webb and Charles Faulkner (1833-1892), a friend from their student days who was now a Mathematics tutor at the university. Whilst at the theatre one evening Rossetti ‘discovered’ local sisters Jane and Bessie Burden and they became models for the murals – their haunting beauty capturing the spirit of the Pre-Raphaelite style.

MORRIS, MARSHALL, FAULKNER & CO.

‘WHATEVER YOU HAVE IN YOUR ROOMS THINK FIRST OF THE WALLS; FOR THEY ARE THAT WHICH MAKES YOUR HOUSE AND HOME.’

Putting up much of the capital himself, William Morris set up a studio and showroom at 8 Red Lion Square. In those early years, ‘The Firm’ as it became known, concentrated on stained glass and other ecclesiastical arts for church decoration such as metalwork, furniture, embroidery and murals. Morris denounced the popular, heavy-handed renovations of old churches, but found plenty of work in refurbishing them or decorating the new churches rapidly being built. Initially outsourcing to other companies, production was brought in-house only when partners had mastered the necessary skills and they had acquired workshops large enough.

The Firm began to appear at international exhibitions and receive awards such as for stained glass and furniture at the 1862 International Exhibition. In 1867 The Firm was asked to decorate the Dining Room at the South Kensington Museum (later the Victoria and Albert Museum), and the Armoury and Tapestry Rooms at St. James’ Palace. These two significant commissions brought prestige and recognition, and secured the future of the business.

BLOCK-PRINTED WALLPAPER

In 1862 Morris focused on designing wallpapers, starting with ‘Daisy’, ‘Fruit’ and ‘Trellis’ which were printed using wood-blocks in 1864. The pear-wood blocks were hand cut and prepared by the specialist firm, Barretts of East London. The design was chiselled into the block and for fine lines and detailing, metal strips or pins were pressed into the wood. Morris appointed wallpaper manufacturer Jeffrey & Co. to print the papers, which they did until 1926. Under the watchful of eye of Managing Director Metford Warner, an area within the factory was reserved just for the production of Morris & Co. wallpapers’ and Warner and Morris worked closely together until each paper was exactly as Morris wanted it. Finding inspiration in the gardens and wild hedgerows of England, Morris captured the randomness and beauty of nature in patter.

The Jeffrey log books, dating from the late 1860s to 1919, contain 309 entries which are numbered sequentially by production. These reference books provide accurate colour samples taken from every paper as it came off the production line, with notes from the printer relating to colour requirements or tone. Morris was always sought for approval on the colour and design prior to production, and he would receive samples during the proofing ‘strike-off’ stage which he returned to Warner, with further instructions if necessary.

William Morris favoured mineral based natural dyes over the synthetic modern equivalents popular in the 1860s, because they were true to the medieval tradition and ‘aged’ beautifully. However, some of the pigments used, such as arsenic (found in the colour green), were discovered to have lethal side-effects. Early Morris wallpapers have been found to contain these toxins but later colours were modified and attempts were made to allay customers’ concerns about safety through advertising.

One of Morris & Co.’s most important commissions was to redecorate the entrance and banqueting rooms of St. James’ Palace. The resulting paper, known as ‘The St. James’, was installed in 1880 and printed with highlights in gold and silver. It required 68 printing blocks to create the repeating pattern over two wallpaper widths and a vertical pattern repeat of 127cm.

In the 1880s Japan was exporting heavily gilded and richly coloured ‘leather papers’ to the British market. At Morris & Co., these exclusive papers were applied to specially designed four-fold screens, created by Dearle. By 1885 Jeffrey & Co. had perfected a process to replicate Japanese leather papers and became the first British company to manufacture, sell and distribute these much sought after affordable alternatives. The process involved block printing on ‘foiled’ paper, lacquering, stamping and stencilling in oil colour.

In 1887 Queen Victoria commissioned Morris & Co. to design wallpaper for Balmoral Castle with the VRI cipher incorporated into the design.

During his career, Morris designed 46 wallpapers and four ceiling papers, amassing to half the total patterns released by the company. Designs for wallpaper were sometimes revisited or used for future projects. ‘Trellis’ wallpaper, inspired by the garden at Red House, was used in May and Jenny Morris’s nursery at their next home in Queens Square, and ten years later in Morris’s bedroom in Kelmscott House, Hammersmith. The design was also adapted into bed hangings for Morris’s bedroom at Kelmscott Manor, embroidered onto a linen cloth by May Morris and friends between 1891-4.

CERAMICS

‘I SHOULD SAY THAT THE MAKING OF UGLY POTTERY WAS ONE OF THE MOST REMARKABLE INVENTIONS OF OUR CIVILISATION’.

In the 1860s Morris began importing ‘blank’ white tiles from Holland. The designs, created by William de Morgan, Morris, Burne-Jones, Rossetti, Brown and Webb, were then hand painted by Kate and Lucy Faulkner and Georgiana Burne-Jones. The first popular design was ‘Daisy’, produced in 1862, and derived from the embroidered hangings from Red House. As with all his endeavours, Morris became interested in the techniques necessary to create the products and learnt about glazes and enamels, inspired by early Delft tiles. A kiln was installed in the basement of 8 Red Lion Square.

Although never a partner of ‘The Firm’, William de Morgan supplied ceramics. Through constant experimentation, de Morgan re-discovered the techniques of lustreware using metal oxides in the firing process. By the 1870s all ceramic tile production was outsourced to de Morgan’s own pottery. His beautiful vases, bowls and plates were later sold through the Morris & Co. Oxford Street showroom and his tiles were typically sold for use on furniture such as washstands and fireplaces, or as large patterned panels made up of a series of tiles, such as the Artichoke Tile panel designed in 1876.

At the other end of the scale, the housing boom of the 1880s and ‘90s created a huge demand for tiles which provided a cheap and hygienic wall-covering for large housing estates and public buildings. However, competition was steep as machine manufacturing was already well-established in Britain.

William and Jane’s eldest daughter Jenny posed for many of The Firm’s early art works, in particular a panel of tiles called ‘The Angels of Creation’ designed by Burne-Jones for a church in Staffordshire. Tragically, after a promising childhood likely to have led to her attending Oxford or Cambridge University, Jenny developed epilepsy in 1876, and her adult life was spent in almost constant ill-health, debilitated by her condition.

FURNITURE

Before Red House, Morris’s interest in furniture began as a student when he furnished his lodgings by making a large but elementary medieval inspired table, settle and set of chairs.

Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. set up a furniture workshop in Great Ormond Yard in London and in the 1860s The Firm launched the ‘Sussex Chair’. With a rush seat and ebonised frame, this simple piece of furniture became one of the most iconic items within the entire range. Bought in huge numbers, the Sussex Chair was also favoured by the partners for use in their homes.

Morris categorised furniture into two groups: ‘work-a-day’ and ‘state furniture’. Unlike the popular Victorian style of fussy and often superfluous pieces, Morris’s furniture was always purposeful, simple and handmade with construction methods intentionally on show. ‘State’ furniture referred to the grander, solid oak sideboards and cabinets, often stained black or green, decorated with panels in stamped leather, lacquered or painted in gesso or oil.

The early work-a-day furniture was often designed by Ford Madox Brown, whilst Rossetti was responsible for more English country furniture and Webb concentrated on state furniture with pared-down Gothic ornament. Originally made by a local cabinet maker in Great Ormond Yard, The Firm also employed apprentices from the Euston Road Boys Home. Hand painting was carried out by Brown, Rossetti and Morris. Furniture first created to furnish Red House was often revisited by Webb. Sideboards in painted and ebonized wood with leather panels and settles with canopies were decorated and painted in gilt by Kate Faulkner and John Henry Dearle.

The ‘Morris’ adjustable chair was designed in 1866 by Webb who adapted the design from a prototype discovered by Warrington Taylor, The Firm’s manager at the time. Available in plain or ebonized wood and with chintz or velvet upholstery, this piece was copied by Heals and Liberty, and also by Stickley, a furniture maker and exponent of the Arts and Crafts style in America. The popular ‘Morris’ chair was still in production in 1913.

EMBROIDERY

Whilst he was a student, Morris taught himself medieval stitch techniques by unpicking old embroideries. After completing the Daisy wall hangings at Red House, embroidery commissions became a significant part of the business, initially for church interiors but expanding to wealthy private households.

One of the first accolades The Firm achieved was awarded to Jane Morris for an embroidery entered in the 1862 International Exhibition, although critics were dubious about the demand for embroidered hangings in a middle-class market. Designs were often inspired by subjects from medieval manuscripts and were uncommercial with motifs that incorporated text with a moral message.

In later years Morris & Co. sold embroidery designed by Morris, his daughter May, and John Henry Dearle, as completed panels or as ‘kits’ to be worked on at home. In 1885, at the age of just 23, May Morris was put in charge of embroidery production. From her home at 8 Hammersmith Terrace, May and her team of female workers, mostly sisters or wives associated with the company, produced a wide variety of goods including fire-screens, workbags, cushion covers, folding screens, table linen and door curtains. She published Decorative Needlework in 1893 and with a lecture tour in America at the end of 1909 did much to raise the profile of this traditionally lowly art form.

GLASS

Commissions for stained glass church windows contributed much of the early output of The Firm and were carried out mainly by Burne-Jones and Madox Brown. The windows at St. Martins in Brampton, Cumbria are particularly stunning examples. They often used designs several times in different commissions – a figure of an angel in a church window may re-appear as a musician for example, minus wings, when used in a private house.

On a smaller scale, Philip Webb (who had designed drinking glasses for Red House) inspired an early range of Morris & Co. tableware made by James Powell’s glassworks in Whitefriars – the suppliers of glass for Burne-Jones’s windows. Morris also learnt the practice of glass blowing

RED HOUSE IS SOLD

‘IF A CHAP CAN’T COMPOSE AN EPIC POEM WHILE HE’S WEAVING A TAPESTRY, HE HAD BETTER SHUT UP….’

Webb had been asked by Morris to design an extension for Red House to accommodate their friends, the Burne-Joneses. However, following the tragic death of Georgiana Burne-Jones’s second son in the winter of 1864, aged only three weeks, they pulled out of the plan and the family moved to 41 Kensington Square with great sadness. Disillusioned by the collapse of his dream, William and Jane sold Red House and moved back to London in 1865, settling at 26 Queen Square with Jenny and May. The business, having outgrown its first premises, was also relocated to their new home.

Morris published a collection of poems with a strong anti-industrial message called ‘The Earthly Paradise’ in the late 1860s and it became an immediate best seller. He hand cut 50 woodblocks for the publication, a task no doubt aided by his experience working on blocks for wallpaper printing.

In 1871 he took out a joint lease on Kelmscott Manor in Lechlade, Gloucestershire, with Rossetti. The picturesque stone manor house provided his children with a retreat in summer holidays to enjoy freedom and fresh air. However, it was a tortuous place for Morris as it gave Rossetti and Jane a haven in which they could conduct their affair in privacy.

Morris had always been fascinated by the legends and myths of Iceland and Norway. He now absorbed himself in a new project by learning Old Icelandic so that he could read these stories in their original language and then translate them for publication in English. He made several trips to Iceland to visit sites from these old sagas.

MORRIS & CO.

‘MY WORK IS THE EMBODIMENT OF DREAMS’.

A poor business structure and internal animosity led William Morris to bring Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. to a close in 1875 and start anew under the name Morris & Co. This gave more control to fewer partners, with Edward Burne-Jones and Philip Webb continuing in their roles.

With the growing popularity of books, public lectures and articles offering advice on household management and good taste, a new type of consumer emerged in the second half of the 19th century. Until this time it was the role of the upholsterer to source papers on behalf of the client who often had little control of the choice. Seizing an opportunity, it wasn’t long before Morris pioneered a new type of retail experience offering a choice of ways to buy. Morris opened his first showroom (incorporating shop and office) at 449 Oxford Street in 1877 which brought the full range under one roof. Now the customer could visit the showroom personally.

In spacious and comfortable surroundings, the fabrics and wallpapers priced for the middle class market and upwards, were ‘presented’ on ‘Standbooks’ by well-informed showroom assistants, priced for the middle class market and upwards. A roll of wallpaper could be retrieved to show the client a larger piece before they made their choice. Customers could also take away a smaller ‘table book’ to decide at home.

Situated in this highly fashionable district, close to Liberty and Heals, people flocked to the showroom to buy the complete Morris & Co. ‘look’ including ceramics by William de Morgan, lighting by W.A.S. Benson and glass by James Powell, as well as smaller items such as photograph frames and embroidered bell-pulls, bags and cushions.

With a solid business format incorporating marketing and sales, customers could either rely on the full interior decorating service or buy via mail-order with confidence. Advice in the mail-order brochure was also designed to assist:

“You must decide for yourself whether the room most wants stability and repose, or if it is too stiff and formal. If repose be wanted, choose the pattern, other things being considered, which has a horizontal arrangement of its parts. If too great a rigidity be the fault, choose a pattern with soft easy line, either boldly circular or oblique wavy – say ‘Scroll’, ‘Vine’, ‘Pimpernel’, ‘Fruit’.”

Agents in America, Europe and Australia drove new business overseas and export sales rose dramatically despite the hefty duties imposed upon the shipments, such was the buying power of the international customers.

MERTON ABBEY MILLS

‘IT IS THE ALLOWING OF MACHINES TO BE OUR MASTERS AND NOT OUR SERVANTS THAT SO INJURES THE BEAUTY OF LIFE NOWADAYS.’

The mid 1870s marked the beginning of the most prolific decade in the history of Morris & Co. All the ranges were expanded and workshops were quickly outgrown. In 1881 William Morris acquired land with outbuildings at Merton Abbey in South London and relocated all the workshops to one location. The buildings were easily modified for the requirements of production. Morris had just become interested in printing his own textiles and Merton Abbey was situated on the River Wandle which had plentiful water, necessary for the hand dyeing and printing of fabrics. The good working conditions in a pleasant environment and above average pay meant the Merton Abbey Mills workers made a good living once they had been fully trained.

Manufacturing also encompassed carpets, tapestries, embroidery and stained glass.

CARPETS

In 1878 Morris gave up his London home in Queen Square and leased a new house in Hammersmith overlooking the Thames, naming it Kelmscott House. The hand-knotting of carpet was not practised in Britain at this time and Morris wanted to reintroduce the art and bring the beauty and mysteries of foreign lands to a British market. By studying Persian rugs, Morris honed his skills and techniques by making small rugs at home. He installed large looms in the coach house and stable at Kelmscott House and started producing ‘Hammersmith’ rugs in 1879, so-called to distinguish them from the cheaper ‘Kidderminster’, ‘Wilton’ and ‘Brussels’ machine-made carpets which Morris & Co. outsourced at the time.

At Merton Abbey, the looms were set up to be operated by six women who were expected to complete 2 inches per day. The work was slow and expensive but costs were off-set by savings made in the machine produced range.

TAPESTRY

In 1878 Morris installed a tapestry loom in his bedroom at Kelmscott House and embarked on what he called ‘the noblest of all the weaving arts’. After studying ancient textiles at the South Kensington Museum, Morris’s first project was ‘Acanthus and Vine’, which took 516 hours to complete. Always using naturally dyed yarns, tapestry weaving was established at Merton Abbey Mills and Morris appointed John Henry Dearle (1860-1932) to manage production. Dearle had joined the company in 1876 as a young assistant in the Oxford Street showroom. He became a trainee in the stained-glass studio and then moved into tapestry production.

Large tapestry commissions were often designed by Webb, Dearle and Morris in collaboration, and executed by their own experienced weavers on high-warp Flemish style looms which Morris had built. The ‘Forest Tapestry’, bought by the Greek merchant and patron of the arts, Alexander Ionides, at the 1890 Arts and Crafts Exhibition, hung in Ionides’s study in Holland Park. ‘The Quest for the Holy Grail’ was a large series of panels also completed in 1890. These expensive items were not very popular so smaller, affordable panels or cushions were available through the showroom and via overseas agents.

STAINED GLASS

Burne-Jones had become the chief designer of stained glass (creating over 100 drawings throughout his lifetime) and a separate area at Merton Abbey was allocated to his glass workshops. To assist with the scaling-up of drawings for huge works of art such as stained glass and tapestry, Morris made use of new technology and the expertise of the photographer Hollyer who provided the negatives for the copying of designs. Morris & Co. dominated British stained glass production during the 1870s and 1880s.

GEORGE JACK FURNITURE

Furniture production was relocated to Merton Abbey Mills in 1881 and then in 1890 to a factory in Pimlico, acquired from Holland & Son and managed by Webb’s assistant George Jack (1855-1931). Jack became chief designer for Morris & Co. the same year and was responsible for much of the in-laid cabinet and upholstered furniture produced.

After Morris’ death in 1896, George Jack and W.A.S. Benson ran the furniture operations and so began a gradual departure from Morris’ vision for simple medieval style furniture made popular by Webb. The fashion had changed to the more conservative Georgian style and so the business began producing more delicate mahogany and walnut furniture.

METALWORK

Morris preferred medieval inspired simple bare-brick fireplaces and free-standing grates, with copper hoods designed by Webb, as seen in Red House. The end of the 19th century saw a renewed interest in metalwork with visible construction, new enamelled copper and unfussy decoration. The established, fine metal-worker and cabinet maker, W.A.S. Benson, was asked to contribute to Morris & Co. Operating from his Fulham workshop and then moving into larger premises near the Morris & Co. showroom, he ventured into machine production after 1896.

With the arrival of electricity at the end of the 19th century, the opportunity for new light fittings became a lucrative area of development.

Throughout the 1880s Morris continued to make a significant contribution to the designs for wallpapers, creating 16 of the 21 patterns released by Morris & Co. in this decade alone, such as ‘Willow Boughs’, ‘Garden Tulip’ and ‘Bird & Anemone’.

The investment that secured and equipped Merton Abbey paid off as, within a few years, production was at its highest across all departments, and workers struggled to keep up with demand.

Morris handed control of Merton Abbey over to his assistant, John Henry Dearle, in the late 1880s. By this time Dearle was also designing wallpapers and fabrics and he produced some of Morris & Co.’s most enduring patterns, often attributed to Morris himself.

PRINTED TEXTILES

In 1868 The Firm issued three 1830s chintzes originating from Bannister Hall and had them block printed by Thomas Clarkson. Disappointed by the results and wanting to understand the processes involved, Morris experimented with vegetable and mineral dyes with Thomas Wardle in Staffordshire. He favoured natural dyes which aged beautifully and faded evenly which were in line with medieval practices. His first design was ‘Jasmine Trail’ circa 1870 but he favoured his second design ‘Tulip & Willow’ which was printed by Thomas Wardle in 1873.

With the acquisition of Merton Abbey Mills, Morris was able to start dyeing and printing his own textiles. He re-introduced the technique of indigo discharge block-printing, first with Prussian blue and then with indigo dyes. In this notoriously difficult method, the indigo is only activated when the cloth is lifted out of the dye bath and exposed to the air. Morris spent hours working with the printers, often with his arms dyed blue up to the elbows, until he achieved the right balance of colour. After the cloth is dyed, the design is block printed with a bleaching agent which lifts some of the blue to produce a paler tone and thereby creating a pattern. The plant, madder, was also used to create red fabrics in the same way.

Having mastered the art of pattern-making through his wallpaper designs, he was also able to understand how a pattern plays on a flat surface or as a pleated curtain.

Printed velveteen was popular in the second half of the 19th century and Morris & Co. produced a number of printed velvets which became popular as an upholstery fabric

WOVEN TEXTILES

Morris fully understood how to create texture when different yarns were mixed together and woven into cloth. Silk, wool and mohair were all used and Morris achieved spectacular results; sometimes patterns were also embellished with gold threads. However, most of the weaves were flat jacquards in wool and were popular for curtains and lining walls; Morris didn’t recommend their use for upholstery as the cloth tended to wear out quicker than chintz.

‘The Bird’ fabric, originally designed by Morris in 1877 for hanging in Kelmscott House, was a complicated, reversible double cloth constructed from two warps and two wefts. ‘Peacock & Dragon’ designed the same year was a popular and imposing flat weave. Sales were despatched to all corners of the world to a hungry market undeterred by the scale of the design which needed generously proportioned rooms to do the fabric justice.

Operated by hand, the jacquard looms partly automated the weaving process, but large commissions had to be outsourced to companies using steam powered looms who could fulfill orders quickly.

SOCIETY FOR THE PROTECTION OF ANCIENT BUILDINGS, THE SOCIALIST LEAGUE AND THE KELMSCOTT PRES

With the operation of Merton Abbey Mills the responsibility of John Henry Dearle, Morris was free to pursue other interests. In an effort to combat the heavy-handed renovations of old churches spreading throughout the country, he co-founded with Philip Webb, the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), which championed the sensitive restoration and conservation of ancient buildings. SPAB is still a significant force in heritage preservation and, like the National Trust, is a recognised and accepted part of life today, but at the time it was a radical idea shared only by a few pioneers.

Morris pursued his political interests and campaigned against poverty by joining the socialist movement and setting up The Socialist League in the 1880s. This revolutionary organisation rejected capitalism and Morris gave his support through public speaking and publishing newspapers to further the cause.

He returned to literary works and set up his own publishing company. The Kelmscott Press, formed in 1891, was based in Hammersmith, under the mentorship of Emery Walker, neighbour, friend and founder of the Doves Press. Beautifully illustrated by Burne-Jones, the books were printed and bound in the medieval style. The output of over 50 works was to be Morris’s opus and is widely regarded as the finest collection in the private press movement. The Kelmscott Press was dissolved in 1898.

A NEW ERA

William Morris died on 3rd October 1896 aged 62 and was buried in the churchyard near his favourite home, Kelmscott Manor, in Gloucestershire. Famously, one doctor at the time said ‘the disease is simply being William Morris and having done more work than most ten men.’

In his will he gave permission for Morris & Co. to be sold:

“I expressly empower my trustees to realise or postpone the realisation of my interest in the business of Morris & Co. I further authorise my trustees, either jointly or concurrently with the partners or surviving partner therein to sell the said business by private contract, tender or auction.”

Dearle continued to manage the Merton Abbey workshops, but overall control of the company went to W.A.S. Benson, with Frank and Robert Smith (long-standing business managers) in deputy roles. Tragically, just two years later, Edward Burne-Jones died and this combined loss brought a down-turn in the fortunes of Morris & Co.

Lacking strong leadership and creative direction, the company was sold in 1905 to Henry Currie Marillier who changed the name to Morris & Co. Decorators Ltd. With much of the artistic talents gone, the core principles were being eroded too. The board decided to launch five wallpaper designs printed by surface roller machines (‘Carnation’, ‘Merton’, ‘Oak Tree’, ‘Tomtit’ and ‘Thistle’) and although similar in appearance to hand block prints, it was a huge departure from the Morris vision. However, the decision proved profitable and the company enjoyed a brief uplift.

In 1911 the Royal Warrant was granted to Morris & Co. Decorators Ltd., in recognition of the many royal commissions undertaken over some 30 years.

In 1917 the Oxford Street showroom was moved to 17, George Street near Hanover Square, but war years limited resources for production and Merton Abbey was partially shut down. The fabric printing was outsourced to Stead McAlpin in Carlisle.

Prudent times inspired a move towards simplicity in decoration and saw the arrival of the first collection of Morris & Co. Plain Wallpapers. However, the production methods were geared only to bespoke wallpapers and the unnecessarily complicated process made these simple papers an expensive hand-finished product.

TURBULENT TIMES

With another name change in 1925 to Morris & Co. Art-workers Ltd, the business was still troubled by dwindling sales and a lack of available resources. With no new designers entering the workforce, they reproduced what they already had – still only five wallpapers as surface prints and the rest as hand block papers. They introduced services such as tapestry repair and even carpet cleaning to keep the interior decorating business going.

In 1926 Jeffrey and Co. was acquired by the Wallpaper Manufacturers Ltd. (WPM) to which Arthur Sanderson and Sons belonged, and the Jeffrey papers were sold through Sanderson’s Berners Street showroom. At that time the WPM controlled almost all the wallpaper manufacturing in the UK. One year later, production of all Jeffrey and Co. papers moved to Sanderson’s own factory in Chiswick, including block prints. After a fire the following year, all Morris & Co. log books, records and match pieces were moved again to Sanderson’s new wallpaper factory at Perivale, although it wasn’t fully operational until 1930.

In 1932 John Henry Dearle died. The last remaining member of Morris’s original team, Dearle had worked for the company for 54 years. The on-set of the Second World War and a reduced skilled labour force brought further pessimism about the future of the business.

SANDERSON BUYS MORRIS & CO.

On 21st March 1940, Morris & Co. Art-workers Ltd. entered voluntary liquidation. With Arthur Sanderson & Sons already managing the wallpaper printing, they seized an opportunity and bought the entire company for £400, including the George Street showroom and contents, all the wallpaper printing blocks, records, logbooks, stock and original samples.

As Sanderson continued to buy up several other UK manufacturers, it became clear that each brand, including Morris & Co., would be over-shadowed by Sanderson’s own. During World War II the Perivale factory was given over to the war effort to produce tents and camouflage. All capital expenditure ceased.

In 1945, in an attempt to bolster faith in UK production, the wallpaper industry instigated an exhibition with over 200 contributors. Sanderson chose to show ‘The Acanthus’, designed by Morris in 1895, which was featured in the exhibition catalogue.

THE FESTIVAL OF BRITAIN

Government granted permission to Sanderson to launch their first post-war pattern book in 1950, and this was shown at the 1951 Festival of Britain. Sanderson focused on exhibiting the huge breadth of product available using economical machine-printing methods.

Five Morris designs were incorporated into a Sanderson pattern book of surface printed wallpapers (the same five chosen by Marillier in 1905). Although at odds with the simplicity and modernity of the 1950s interior, and indeed the Sanderson house style, Sanderson continued to market the rather unfashionable Morris designs.

THE SWINGING SIXTIES

The Arts and Crafts style did find its place alongside the eclecticism of tastes and looks in the 1960s and started influencing design. It was now that Sanderson, perhaps emboldened by reaching their centenary year, began block printing Morris wallpapers re-coloured by the studio in psychedelic hues.

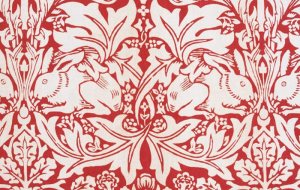

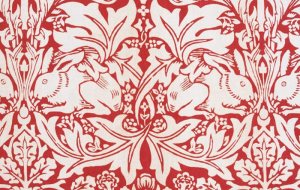

The newly appointed Fabric Design Manager, George Lowe, from the Wall Paper Manufacturers Ltd., decided to launch a new range of five stunning screen-printed fabrics, in tandem with the wallpapers, and were sold directly to Heals and Habitat. Previously only available on paper, the designs were ‘Marigold’, ‘Vine’, ‘Chrysanthemum’, ‘Golden Lily’ and ‘Bachelors Button’ and were shown among known fabrics such as ‘Brer Rabbit’ and ‘Willow Bough’. A green and turquoise colourway of ‘Bachelors Button’ was shown on the front cover of the Sanderson company magazine Vista. The Berners Street showroom even wore clothing in the fabrics and the dressed room sets became more daring in their presentation of the Morris brand.

With the wallpaper factory in Perivale and the fabric printing mills in Uxbridge producing separate ‘Morris’ collections, albeit branded under Sanderson, the Morris name took on a new lease of life matched by growing demand.

Furnishing fabrics started to out-sell wallpaper for the first time, owing to two key factors. The introduction of the Clean Air Act for household fuels meant homeowners no longer needed to regularly redecorate their pollution damaged walls. The continuing trend for the simple Scandinavian look called for painted rather than papered walls. Sanderson’s ‘Our Man’ advertising campaign – a marketing strategy in the 1960s – cited that as Morris was a ‘great artist’ and ‘genius’ Sanderson ‘consider it a privilege to give his designs wider circulation’. Trying to inspire new interest in the wallpapers, they proudly promoted the authenticity of the product, hand-printed in ‘modern colour ways’ using the original wood blocks.

With the screen printed fabrics thriving in the marketplace and a Victoriana revival filtering down through popular culture and fashion, as well as design, Sanderson began to publicise the ranges in non-commercial areas and approached the William Morris Society, established in 1955. The Society printed advertisements promoting the new block printed wallpapers in its Journal but one wonders at the reaction of the unusual Morris look among his devotees.

THE 1970S

The high costs of producing the Morris block printed wallpapers caused overheads to rise at Perivale so the factory tried to ease the strain on the business by undertaking profitable commissions and offering bespoke colourways. They also adapted some wood block designs into screen prints to reduce labour costs.

Despite advertising, wallpaper sales were being left behind by the demand for furnishing fabric which was only exacerbated by the significant arrival of a second Morris fabric collection in 1975. A new brown colourway of ‘Golden Lily’, designed by John Henry Dearle in 1899, saw sales reaching 5,000 metres per month. As with ‘Chrysanthemum’, designed by Morris in 1877, their phenomenal success in the 1970s has kept the designs in the public conscience, and in the pattern books, ever since.

Celebrity endorsement was prevalent in the advertising campaigns of the 1970s, featuring personalities such as Joan Bakewell in her home, decorated in Morris’s 1897 design ‘Net Ceiling’.

Sanderson’s own revolutionary ‘Triad’ coordinated range, first launched in 1962, had been so successful it secured Sanderson’s place at the forefront of the UK furnishings industry. Triad (now called ‘Options’) brought fabrics and wallpapers together in one book and in the 1970s started to include Morris designs, such as ‘Blackthorn’, ‘Rose’ and ‘Myrtle’. Another first was the inclusion of photography on the cover and inside the pattern books. With well-designed layouts, the books helped the consumer easily achieve the coordinated look, a popular interiors trend in the 1970s and 80s.

Sanderson released yet more vibrant colourways of Morris designs in a new ‘Heritage Collection’ wallpaper pattern book in the late 1970s, which appeared alongside patterns by C.F.A. Voysey and Owen Jones. With hand block and screen printed wallpaper sales already floundering, the book was unable to cause any reprieve and even damaged their reputation among Morris purists.

THE 1980S AND 1990S

With slowing demand for wallpapers, the Perivale factory shut; however, a small block printing unit remained until the late 1980s. With the arrival of A. L. Taylor as Chief Executive in 1982, Sanderson Wallcoverings and Sanderson Fabrics divisions were consolidated into one business, thereby streamlining costs and combining resources, sales and the design studios. Marketing became the driving force behind a more cohesive business strategy which focussed on the Sanderson brand rather than a need to be multifarious.

An archive was built at Uxbridge specially designed to house the vast resource of Sanderson and Morris original samples, log books and reference material. Invaluable to the design studio and marketing teams, the archive has become a cornerstone of Morris & Co. today.

Michael Parry replaced George Lowe as Design Manager in 1982. Previously in the role of Merchandising Manager, Parry instigated the move to sever Morris & Co. from Sanderson, resurrecting its own brand identity for the first time in 45 years, beginning with the release of Morris & Co. block printed wallpapers authentically reproduced from the originals. More significantly, at the same time, Parry arranged to have long-established block-print designs transferred onto surface rollers which were printed by Fiona Wallpapers in Denmark. Technology had advanced considerably since Morris’s time and by slowing the rollers down, Parry achieved a good quality and competitively priced machine printed wallpaper with the appearance of a block print.

The arrival of the first book of coordinated Morris & Co. machine-printed fabrics and wallpapers in 1984 was launched at a new ‘Morris Room’ at the Berners Street showroom. High demand led to subsequent volumes of the co-coordinated books which in turn ensured the future success of the Morris & Co. business.

By the end of the 1980s, the Morris & Co. brand was extricated from Sanderson completely, and marketed separately to strengthen both names within the UK furnishings industry. In a 1991 survey, public perception held Sanderson as market leader whilst Marks & Spencer, John Lewis, Morris & Co. and Liberty were not far behind.

Opportunities to bring more Morris pattern into the home inspired several lucrative licensing deals with partners in the UK and America. ‘Willow Bough’, a design from 1887, was now available as bedlinen, tableware, block printed wallpaper, printed textile, printed sheer, upholstery jacquard, tapestry and in 1990 as a surface printed wallpaper.

The small wallpaper block-printing unit at Perivale was moved up to Lancashire when a new factory was acquired. With the local workforce trained in the art of hand printing paper, another collection was launched in 1990. Gradually and strategically, the Sanderson name was removed from all Morris & Co. merchandise and advertising, and by 1995 Sanderson had ceased to include any Morris patterns in its own collections.

THE 21ST CENTURY

In 2003 Sanderson and Morris & Co. were purchased by Walker Greenbank PLC, headed by John Sach. Production was moved again, this time to the Group’s own mills: wallpaper manufacture to Anstey in Loughborough and fabric printing to Standfast and Barracks in Lancaster. Heavy investment in the UK and export markets, together with strong advertising and increased stock, invigorated sales.

Since 2000 Morris & Co. have been releasing fabric and wallpaper collections approximately every two years and in 2007, after nearly a century, re-introduced embroidery.

Morris & Co. celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2011 with a new collection of archive based prints, weaves, embroidered fabrics and surface-printed wallpapers, along with new designs inspired by the life and work of William Morris and his circle.

The current craft revival movement, and on-going interest in our design heritage, means the Morris & Co. brand continues to reach new audiences and find new markets as support for British manufacturing industries grows.

Morris & Co. fabrics and wallpapers are supplied through high quality interior designers or found at department stores and retailers throughout the UK. Royalties from licensees continue to make a significant contribution to profits, whilst international sales represent almost 40% of the Company’s turnover with major markets established in over 60 countries worldwide including Japan, Australasia, the United States and Russia. These sales are driven by an experienced network of agents and distributors, some of whom Sanderson have worked with for over 40 years.