Octavia Hill (3 December 1838 – 13 August 1912) was an English social reformer, whose main concern was the welfare of the inhabitants of cities, especially London, in the second half of the nineteenth century. Born into a family with a strong commitment to alleviating poverty, she herself grew up in straitened circumstances owing to the financial failure of her father. With no formal schooling, she worked from the age of 14 for the welfare of working people.

Hill was a moving force behind the development of social housing, and her early friendship with John Ruskin enabled her to put her theories into practice with the aid of his initial investment. She believed in self-reliance, and made it a key part of her housing system that she and her assistants knew their tenants personally and encouraged them to better themselves. She was opposed to municipal provision of housing, believing it to be bureaucratic and impersonal.

Another of Hill’s concerns was the availability of open spaces for poor people. She campaigned against development on existing suburban woodlands, and helped to save London’s Hampstead Heath and Parliament Hill Fields from being built on. She was one of the three founders of the National Trust, set up to preserve places of historic interest or natural beauty for the enjoyment of the British public. She was a founder member of the Charity Organisation Society (now the charity Family Action) which organised charitable grants and pioneered a home-visiting service that formed the basis for modern social work. She was a member of the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws in 1905.

Hill’s legacy includes the large holdings of the modern National Trust, several housing projects still run on her lines, a tradition of training for housing managers, and the museum established by the Octavia Hill Society at her birthplace.

Biography

Early years

Octavia Hill was the daughter of James Hill, corn merchant and banker, and his third wife, Caroline Southwood Smith. He had been widowed twice, and had six children (five daughters and a son) from his previous marriages. He had been impressed by the writings on education of Caroline Southwood Smith, the daughter of Dr Thomas Southwood Smith, a pioneer of sanitary reform. He had engaged Caroline as a governess for his children in 1832, and they were married in 1835, three years before Octavia was born in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, her father’s eighth daughter and ninth child. The family’s comfortably prosperous life was disrupted by James Hill’s financial problems and his mental collapse. In 1840 he was declared bankrupt. Caroline Hill’s father gave the family financial support, and took on some of Hill’s paternal role. Southwood Smith was a health and welfare reformer concerned with a range of social issues including child labour in mines and the housing of the urban poor. Caroline Hill held similar views on social reform, and her interest in progressive education, influenced by Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, and Southwood Smith’s daily experience in his work at the London Hospital in the East End inspired Octavia Hill’s concern for the poorest in early Victorian London. She received no formal schooling: her mother educated the family at home.

The family settled in a small cottage in Finchley, now a north London suburb, but then a village. Octavia Hill was impressed and moved by Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor, a book that portrayed the daily lives of slum dwellers. She was also strongly influenced by the theologian, Anglican priest and social reformer F. D. Maurice, who was a family friend. She began her work on behalf of London’s poor by helping to make toys for Ragged school children, and serving as secretary of the women’s classes at the Working Men’s College in Bloomsbury in central London.

A co-operative guild providing employment for “distressed gentlewomen” accepted Hill for training in glass-painting when she was 13. When the work of the guild was expanded to provide work in toy-making for Ragged school children, she was invited, at the age of 14, to take charge of the workroom. The following year she began working in her spare time from the guild as a copyist for John Ruskin in Dulwich Art Gallery and the National Gallery. She was deeply aware of the dreadful living conditions of the children in her charge at the guild. Her views on encouraging self-reliance led to her association with the Charity Organisation Society (COS), described by Hill’s biographer Gillian Darley as “a contentious body which deplored dependence fostered by kindly but unrigorous philanthropy … support to the poor had to be carefully targeted and efficiently supervised. Later in life, however, she began to think the COS line … was over-harsh.”

Hill was short, like all her family, and indifferent to fashion. Her friend Henrietta Barnett wrote: “She was small in stature with long body and short legs. She did not dress, she only wore clothes, which were often unnecessarily unbecoming; she had soft and abundant hair and regular features, but the beauty of her face lay in brown and very luminous eyes, which quite unconsciously she lifted upwards as she spoke on any matter for which she cared. Her mouth was large and mobile, but not improved by laughter. Indeed, Miss Octavia was nicest when she was made passionate by her earnestness.” Barnett also spoke of Hill’s streak of ruthlessness. Gertrude Bell called Hill despotic. Later in Hill’s life, the Bishop of London, Frederick Temple, encountered her at a meeting of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, and wrote, “She spoke for half an hour … I never had such a beating in all my life.”

Housing for the poor

Parliament and many concerned reformers had been attempting to improve the housing of the working classes since the early 1830s. When Hill began her work, the model dwelling movement had been in existence for twenty years, royal and select committees had sat to examine the problems of urban well-being, and the first of many tranches of legislation aimed at improving working class housing had been passed. From Hill’s point of view these had all failed the poorest members of the working class, the unskilled labourers. She found that their landlords routinely ignored their obligations towards their tenants, and that the tenants were too ignorant and oppressed to better themselves. She tried to find new homes for her charges, but there was a severe shortage of available property, and Hill decided that her only solution was to become a landlord herself. John Ruskin, who was interested in the co-operative guild, knew Hill from her work as his copyist and was impressed by her. As an aesthete and a humanitarian he was affronted by the brutal ugliness of the slums. In 1865, having inherited a substantial sum of money from his father, he acquired for £750 the leases of three cottages of six rooms each in Paradise Place, Marylebone.

Ruskin placed these houses, which were “in a dreadful state of dirt and neglect”, under Hill’s management. He told her that investors might be attracted to such schemes if a five per cent annual return could be secured. In 1866 Ruskin acquired the freehold of five more houses for Hill to manage in Freshwater Place, Marylebone. The Times recorded, “The houses faced a bit of desolate ground occupied by dilapidated cowsheds and manure heaps. The needful repairs and cleaning were carried out, the waste land was turned into a playground where Mr. Ruskin had some trees planted.”

After being improved the properties were let to those on intermittent and low incomes. A return of five per cent on capital was obtained as promised to Ruskin; any excess over the five per cent was reinvested within the properties for the benefit of the tenants. Rent arrears were not tolerated, and bad debts were minimal. As Hill said, “Extreme punctuality, and diligence in collecting rents, and a strict determination that they shall be paid regularly, have accomplished this.” In consequence of her prudent management, Hill was able to attract new backers, and by 1874 she had 15 housing schemes with around 3,000 tenants.

Hill’s system was based on closely managing not only the buildings but the tenants; she insisted, “you cannot deal with the people and their houses separately.” She maintained close personal contact with all her tenants, and was strongly opposed to impersonal bureaucratic organisations and to governmental intervention in housing. In her view, “municipal socialism and subsidized housing” led to indiscriminate demolition, re-housing schemes, and the destruction of communities.

Housing management

At the heart of the Octavia Hill system was the weekly visit to collect rent. From the outset, Hill conceived this as a job for women only. She and her assistants, including Emma Cons combined the weekly rent collection with checking every detail of the premises and getting to know the tenants personally, acting as early social workers. At first Hill believed, “Voluntary workers are a necessity. They are better than paid workers, and can be had in sufficient numbers.” Later, she found it expedient to maintain a paid workforce. Her system required a large staff. Rent was collected on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday mornings. Rent accounts were balanced in the afternoons and arrangements were made with contractors for repairs. On Thursdays and Fridays arrears were pursued, contractors’ invoices paid, new tenancy lettings and tenants’ moves organised.

If any of Hill’s assistants had spare time, whether during normal working hours or in frequent voluntary after-hours working, it was used to promote tenants’ associations and after-work and children’s after-school clubs and societies. In 1859, Hill created the Southwark detachment of the Army Cadet Force, its first independent unit, which gave training along military lines for local boys. Hill considered that such an organisation would be more like the “real thing” than such existing outfits as the Church Lads’ Brigade and therefore more attractive to young men “who had passed the age of make-believe”. She invited a serving officer of the Derbyshire Regiment to set up the company, and such was its popularity that its numbers had to be capped at 160 cadets.

Hill’s principles were summed up in an article of 1869: “Where a man persistently refuses to exert himself, external help is worse than useless.” She was an outspoken critic of the principles of “outdoor relief” or the Speenhamland system of poor relief as operated by various Poor Law Boards. Because these systems did not encourage recipients to work, she regarded them as “a profligate use of public funds.” Under her methods, personal responsibility was encouraged. She insisted on dealing with arrears promptly; she appointed reliable caretakers; she took up of references on prospective tenants, and visited them in their homes; she paid careful attention to allocations and the placing of tenants, with regard to size of families and the size and location of the accommodation to be offered; and she made no rules that could not be properly enforced.

An American admirer described her as “ruling over a little kingdom of three thousand loving subjects with an iron scepter twined with roses.” Although Hill drove her associates hard, she drove herself harder. In 1877, she collapsed and had to take a break of several months from her work. Darley ascribes a number of contributory causes: “chronic overwork, a lack of delegation, the death of her close friend Jane Senior, the failure of a brief engagement” as well as an attack on her by John Ruskin. The Hill family found a companion for her, Harriot Yorke (1843–1930). Yorke took on a great amount of the everyday work that had caused Hill’s collapse. She remained her companion until Hill’s death. A further palliative was the building of a cottage, at Crockham Hill near Sevenoaks in Kent, where they could take breaks from their work in London.

Open spaces

Among Hill’s concerns was that her tenants, and all urban workers, should have access to open spaces. She believed in “the life-enhancing virtues of pure earth, clean air and blue sky.” In 1883, she wrote:

There is perhaps no need of the poor of London which more prominently forces itself on the notice of anyone working among them than that of space. … How can it best be given? And what is it precisely which should be given? I think we want four things. Places to sit in, places to play in, places to stroll in, and places to spend a day in. The preservation of Wimbledon and Epping shows that the need is increasingly recognised. But a visit to Wimbledon, Epping, or Windsor means for the workman not only the cost of the journey but the loss of a whole day’s wages; we want, besides, places where the long summer evenings or the Saturday afternoon may be enjoyed without effort or expense.

She campaigned hard against building on existing suburban woodlands, and helped to save Hampstead Heath and Parliament Hill Fields from development. She was the first to use the term “Green Belt” for the protected rural areas surrounding London. Three hills in Kent (Mariners Hill, Toys Hill and Ide Hill) which she helped to protect from development form part of the belt.

In 1876 Hill became the treasurer of the Kyrle Society, founded in that year by her eldest sister, Miranda, as a “Society for the Diffusion of Beauty”. Under the slogan “Bring Beauty Home to the Poor” it aimed to bring art, books, music and open spaces into the lives of the urban poor. For a short period it flourished and expanded, and although it declined after a few years, it was a template for the National Trust, 20 years later.

Before that, however, Hill was engaged in a campaign in 1883 to stop the construction of railways from the quarries in the fells overlooking Buttermere, in the English Lake District, with damaging effect on the unspoilt scenery. The campaign was led by Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley, who secured the support of Ruskin, Hill, and Sir Robert Hunter, solicitor to the Commons Preservation Society. From 1875 onwards, Hunter had been Hill’s legal adviser on the protection of open spaces in London. Both he and Rawnsley, building on an idea put forward by Ruskin, conceived of a trust that could buy and preserve places of natural beauty and historic interest for the nation.

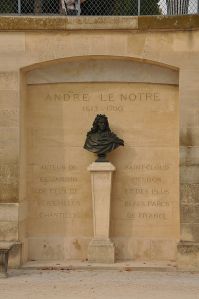

On 16 November 1893, Hill, Hunter and Rawnsley met in the offices of the Commons Preservation Society and agreed to launch such a trust. Hill suggested that it should be called “The Commons and Gardens Trust”, but the three agreed to adopt Hunter’s suggested title, the “National Trust”. Under its full formal title, the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty was inaugurated the following year. The trust was concerned primarily with protecting open spaces and endangered buildings of historic interest; its first property was Alfriston Clergy House and its first nature reserve was Wicken Fen.

Later years

The number of homes managed by Hill continued to grow. Although Ruskin had turned against her in a bout of mental instability, she found a new supporter, the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, who handed over to her the management of their housing estates in several poor areas of south London. By the end of the nineteenth century, Hill’s women workers were no longer unpaid volunteers but trained professionals. Hill’s influence spread beyond the properties under her own control. Her ideas were taken up and copied, with her enthusiastic support, in continental Europe and the United States of America. Beatrice Webb said that she “first became aware of the meaning of the poverty of the poor,” while staying with her sister, who was a rent collector for Octavia Hill in the East End. Queen Victoria’s daughter, Princess Alice of Hesse-Darmstadt, was taken incognito on a tour of some of Hill’s properties, and she translated Hill’s Homes of the London Poor into German. Among those whom Hill trained was her assistant and secretary, Maud Jeffery, who was later engaged by the Commissioners of Crown Lands to run new housing estates in London on Octavia Hill’s lines. Even some local authorities, despite Hill’s distrust, followed her model: some of the earliest examples of municipal council housing, at Kensington and Camberwell, were run on her lines, with the acquisition of working class houses, and their gradual improvement, without evictions or demolitions.

Despite her opposition to interference by national or local government in the provision of housing, Hill had to cope with the newly created London County Council and the involvement of the council and other local authorities in providing housing for the poor. In 1884 a royal commission on the housing of the working classes was set up, but the prime minister, W.E. Gladstone, and his ministerial colleagues vetoed a proposal to include Hill among the members of the commission. The municipal authorities quickly surpassed her in the number of properties under their management. A.S. Wohl notes that in the 1880s Hill had about £70,000 worth of property under her management, and at the end of her career she was managing the dwellings of “perhaps three or four thousand people at the most.” The London County Council, by contrast, had a budget of £1,500,000 for its programme of rehousing London’s poor in 1901–02.

Hill was opposed to other reforms that came about in the early part of the twentieth century. She was against female suffrage on the grounds that “men and women help one another because they are different, have different gifts and different spheres”. She also believed that provision of social services and old-age pensions by the government did more harm than good, sapping people’s self-reliance.

Hill died from cancer on 13 August 1912 at her home in Marylebone, at the age of 73.

Legacy and memorials

When John Singer Sargent’s portrait of her was presented by her fellow-workers in 1898, Hill made a speech in which she said, “When I am gone, I hope my friends will not try to carry out any special system, or to follow blindly in the track which I have trodden. New circumstances require various efforts, and it is the spirit, not the dead form, that should be perpetuated. … We shall leave them a few houses, purified and improved, a few new and better ones built, a certain amount of thoughtful and loving management, a few open spaces…” But, she said, more important would be “the quick eye to see, the true soul to measure, the large hope to grasp the mighty issues of the new and better days to come – greater ideals, greater hope, and patience to realize both.”

The Horace Street Trust, founded by Hill, became a model for many subsequent housing associations and developed into the present trust that bears her name, Octavia Housing. Today it owns several of the homes, including Gable Cottages, designed by Elijah Hoole, who worked with Hill for many years. Hill’s determination to provide community space can still be seen in the shape of the Red Cross site in Southwark (1888), among others. The Octavia Hill Society website states that with a community hall, and soundly maintained attractive houses, Hill here anticipated the fundamental ingredients of town planning by some 15 years.

The Settlement Movement (creating integrated mixed communities of rich and poor) grew directly out of Hill’s work. Her colleagues Samuel and Henrietta Barnett, founded Toynbee Hall, the first university-sponsored settlement, which together with the Women’s University Settlement (later called the Blackfriars Settlement) continues to serve local communities. Overseas, Hill’s name is perpetuated in the Octavia Hill Association in Philadelphia, a small property company, founded to provide affordable housing to low and middle-income city residents.

Women who had trained under Hill formed the Association of Women Housing Workers in 1916. This later changed its name to the Society of Housing Managers in 1948. After merging with the Institute of Housing Managers in 1965, the society became the present day Chartered Institute of Housing in 1994. The CIH is a professional body for those working in the housing profession in the UK and overseas. The training that Hill gave to Charity Organisation Society volunteers contributed to the development of modern social work, and COS continued to be instrumental in developing social work as a profession during the twentieth century. COS is still in operation today as the charity Family Action.

In 1907, Parliament passed the first National Trust Act, enshrining the trust’s permanent purpose and giving it powers to protect property for the benefit of the nation. The trust now looks after a wide range of coast, countryside and historic buildings. According to the trust’s website, “Staff, volunteers and tenants are engaged daily in providing access to open spaces for people’s enjoyment, providing habitats for wildlife and in improving our environment – ‘for ever, for everyone’.”

Commemorations of Hill herself include a monument to her at a Surrey beauty spot, on the summit of a hill called Hydon Ball (now owned by the National Trust). Shortly after her death, the family erected a stone seat there, from which walkers can enjoy views over the Surrey countryside. The Octavia Hill Society was set up in 1992 “to promote awareness of the ideas and ideals of Octavia Hill, her family, fellow workers and their relevance in today’s society nationally and internationally”. Under the society’s auspices her birthplace at Wisbech has been turned into the Octavia Hill Birthplace Museum. In 1995, to mark the centenary of the National Trust, a new variety of rose, “Octavia Hill”, was named in her honour.